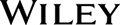

The Maverick and His Machine: Thomas Watson, Sr. and the Making of IBMISBN: 978-0-471-41463-6

Hardcover

528 pages

April 2003

This is a Print-on-Demand title. It will be printed specifically to fill your order. Please allow an additional 10-15 days delivery time. The book is not returnable.

Other Available Formats: Paperback

|

||||||

"...a rich and thorough portrait that goes right back to turn-of-the-century America..." (Business Voice, March 2003)

The story of Watson's transformation of the disorganized, amorphous Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company into steamlined, world-famous IBM receives a spirited telling by Maney, a USA Today technology columnist. Access to previously unexplored records has provided juicy raw material, including letters and internal memos, to bring America's first celebrity CEO to life in this wart-sand-all biography: Watson (1874-1956) saw the strategic value of corporate culture early and was protective of what he built; Maney argues that the strength of that culture later allowed IBM to survive the potentially devastating effects of Watson's personality flaws. Charismatic, optimistic and generous, Watson was also self-absorbed and psychologically ruthless in getting things done his way. Hard to work for and unable to distinguish between the company and himself, he also behaved like a dictatorial CEO when wreaked havoc with his family. Watson's mania for overreaching peaked when he accepted a decoration from Hitler in 1937 under the deluded impression that Hitler woul d follow Watson's ca mpaign for world peace through world trade; according to Maney, that episode illustrates how out-of-control Watson's ego had grown. Yet, as Maney makes clear in this timely tale of the man who made information into an industry and discovered the power of corporate culture, "Watson wasn't just the best business story at the end of the 1930s; he had become a great American success story that captured the popular imagination." Agent, Sandy Dijkstra. (May).

Forecast: Maney's book should hold great appeal not only for avid business readers but also for devotees of the vicissitudes of financial dynasties. That appeal will be supported by a 75,000-copy first printing and a $100,000 ad/promo budget. (Publishers Weekly, March 17, 2003)

"...Maney has written a timely and authoritative biography. Without lapsing into hero worship, he presents a great, if flawed, man in all his humanity." (Business Week, May 12, 2003)

WHEN Thomas J. Watson Jr., who ran the International Business Machines Corporation during its climb to dominance in the computer industry, published his memoirs in 1990, he called the book "Father, Son & Co." His father - who had taken over a motley assortment of business machine companies in 1914 while awaiting sentencing on a criminal antitrust conviction - loomed large in the story. Indeed, one reason the book has become a business classic is surely its poignant, child's-eye view of the flawed yet fascinating father who created I.B.M. and brought it to the brink of the computer age before passing it to his son, who died in 1993.

The portrait of Thomas J. Watson Sr. in his son's memoirs had all of the misty myopia that accompanies any child's perceptions of a fearfully adored parent. One reviewer complained that "we hear too little of life within I.B.M. - and too much of Mr. Watson telling us how awful it was being his father's son."

A much more lively and nuanced picture of the senior Watson can be found in Kevin Maney's excellent new biography, "The Maverick and His Machine: Thomas Watson Sr. and the Making of I.B.M." (John Wiley & Sons, $29.95). Enriched by access to Watson's personal papers from the I.B.M. archives, the book brings this complex man to life and provides a clearer sense of how the I.B.M. culture took shape around one man's quirks, preferences and iron whims.

The company songs, the daily white shirts, the polish and pomp of corporate ceremonies - all of them were manifestations of Watson's own overcompensating insecurities. An awkward young man from a family with little money, he started out in a career that was the punchline of countless American jokes: the traveling salesman. Not until he was hired in 1896 by the National Cash Register Company in Dayton, Ohio, did Watson start to acquire the poise and polish that he would demand of his own executives decades later.

But his career at "the Cash," under the tutelege of its chairman, John H. Patterson, was very nearly his ruin. National Cash Register had a virtual monopoly in the manufacturing and sale of its product, which was becoming increasingly popular among American retailers. Unfortunately, the machines were built so solidly that they rarely wore out. Companies selling secondhand cash registers began to steal business from it.

So, in 1903, Patterson drafted Watson to run an elaborate scam. After ostensibly resigning from the company, Watson set up a chain of used cash register stores that was secretly backed by National Cash Register. By paying more for secondhand machines and selling them for less, Watson drove virtually all of Patterson's competitors out of business. He seems never to have doubted the legality of what he was doing. But when an angry ousted executive started talking to the Justice Department, the scheme figured in a 1912 federal grand jury indictment of Patterson and more than two dozen of his executives, including Watson.

In February 1913, Watson, Patterson and all but one of the other executives were convicted of criminal antitrust violations. Watson, newly married, faced up to a year in prison.

Somehow, in 1914, he nevertheless persuaded an unreconstructed trust-builder named Charles Ranlett Flint to hire him to try to save a rickety business-machine trust that Flint had assembled in 1911. The conglomerate included the Computing Scale Company of America, which made scales that calculated the price of products sold by weight; the International Time Recording Company, which made the time clocks on which workers punched in for the day; and the Tabulating Machine Company, which used punched holes in rectangular cards to sort information - "the forefathers of mainframe computers," notes Mr. Maney, a technology columnist for USA Today.

FLINT called this ailing hodgepodge the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company. And in a remarkable decision - one cannot imagine it being replicated in this post- Enron era - he hired the energetic and supremely confident convicted felon, Thomas J. Watson, to bring the company back to life. Watson, whose conviction was later overturned, succeeded beyond anyone's imagination, except his own. Seeing the future in his little tabulating-machine company, he invested lavishly in research and expanded wildly, even in the face of the Depression.

Mr. Maney observes that "Watson borrowed a common recipe for stunning success: one part madness, one part luck, and one part hard work to be ready when luck kicked in."

The book draws on extensive corporate records to capture Watson's self-absorbed monologues to his senior executives, giving the reader an immense sympathy for the men and women who endured them. With I.B.M.'s cooperation, Mr. Maney seems to have inspected every letter, memorandum and index card that passed through Watson's hands. But the bulkiness of the research only occasionally breaks through the elegant fabric of the storytelling.

Watson - a tyrant in the boardroom, a charmer on the dance floor, a sponge for sycophantic flattery, a genius at selling an idea - emerges as an infuriating, sometimes pathetic but always fascinating business icon. For those who loved "Father, Son & Co.," this is an essential and readable companion book. Call it "I.B.M.: The Prequel." (New York Times, May 12, 2003)

IBM for decades had a distinct corporate personality, and the leader in driving that culture was Thomas Watson, Sr. Other books have described this irascible man, yet this biography by a technology journalist uses recently discovered and wonderfully detailed corporate log books to flesh out his contradictory persona. Watson was a short-tempered tyrant who surrounded himself with yes-men and managed an increasingly complicated company by instinct. Yet he inspired loyalty and enthusiasm through his relentless optimism and willingness to hire ordinary young people and give them a chance. He made IBM one of the first companies to accept women in its training programs, in the1930s no less. And when managers resisted hiring the first women graduates of the programs, he angrily fired every man who graduated the same year. Maney notes that IBM's dominant position in a booming industry may have played a large part in persuading employees to tolerate Watson's unpredictable behavior. But the author's delightful anecdotes showcase the quirky, human side of what became a major knowledge-based company. (Harvard Business Review, May 2003)

"...excellent use of transcripts...should be recommended reading for anyone who seriously wants to be a business mogul..." (Economist, 10 May 2003)

"...formidable in its research, vivid, insightful and often hilarious..." (Management Today, June 2003)

"...an intriguing study of the man who made IBM, Thomas Watson..." (New Scientist, 7 June 2003)

"Maney, a USA Today technology columnist, has written a superb biography of Thomas Watson Sr., who took over the small Computer-Tabulating-Recording (C-T-R) Company in 1914 and fashioned it into the giant corporation we know today as International Business Machines (IBM). Watson had come to prominence for his work at National Cash Register (NCR), but owing to his involvement in a federal antitrust case, was forced out of his job. This might have destroyed a lesser man, but not Watson, who quickly moved on to C-T-T. A lifelong salesman, Watson always paid close attention to his company's customers, but he also felt that employees were equally important, offering high wages and good benefits. Although his management style was often regarded as imperious, he is credited with founding IBM's famous corporate culture, which enabled the company to succeed. As he aged, be became increasingly stubborn and brooked no dissent, which led to some terrible misjudgments, most notably his involvement with IBM's German subsidiary and receipt of a medial from

The story of Watson's transformation of the disorganized, amorphous Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company into steamlined, world-famous IBM receives a spirited telling by Maney, a USA Today technology columnist. Access to previously unexplored records has provided juicy raw material, including letters and internal memos, to bring America's first celebrity CEO to life in this wart-sand-all biography: Watson (1874-1956) saw the strategic value of corporate culture early and was protective of what he built; Maney argues that the strength of that culture later allowed IBM to survive the potentially devastating effects of Watson's personality flaws. Charismatic, optimistic and generous, Watson was also self-absorbed and psychologically ruthless in getting things done his way. Hard to work for and unable to distinguish between the company and himself, he also behaved like a dictatorial CEO when wreaked havoc with his family. Watson's mania for overreaching peaked when he accepted a decoration from Hitler in 1937 under the deluded impression that Hitler woul d follow Watson's ca mpaign for world peace through world trade; according to Maney, that episode illustrates how out-of-control Watson's ego had grown. Yet, as Maney makes clear in this timely tale of the man who made information into an industry and discovered the power of corporate culture, "Watson wasn't just the best business story at the end of the 1930s; he had become a great American success story that captured the popular imagination." Agent, Sandy Dijkstra. (May).

Forecast: Maney's book should hold great appeal not only for avid business readers but also for devotees of the vicissitudes of financial dynasties. That appeal will be supported by a 75,000-copy first printing and a $100,000 ad/promo budget. (Publishers Weekly, March 17, 2003)

"...Maney has written a timely and authoritative biography. Without lapsing into hero worship, he presents a great, if flawed, man in all his humanity." (Business Week, May 12, 2003)

WHEN Thomas J. Watson Jr., who ran the International Business Machines Corporation during its climb to dominance in the computer industry, published his memoirs in 1990, he called the book "Father, Son & Co." His father - who had taken over a motley assortment of business machine companies in 1914 while awaiting sentencing on a criminal antitrust conviction - loomed large in the story. Indeed, one reason the book has become a business classic is surely its poignant, child's-eye view of the flawed yet fascinating father who created I.B.M. and brought it to the brink of the computer age before passing it to his son, who died in 1993.

The portrait of Thomas J. Watson Sr. in his son's memoirs had all of the misty myopia that accompanies any child's perceptions of a fearfully adored parent. One reviewer complained that "we hear too little of life within I.B.M. - and too much of Mr. Watson telling us how awful it was being his father's son."

A much more lively and nuanced picture of the senior Watson can be found in Kevin Maney's excellent new biography, "The Maverick and His Machine: Thomas Watson Sr. and the Making of I.B.M." (John Wiley & Sons, $29.95). Enriched by access to Watson's personal papers from the I.B.M. archives, the book brings this complex man to life and provides a clearer sense of how the I.B.M. culture took shape around one man's quirks, preferences and iron whims.

The company songs, the daily white shirts, the polish and pomp of corporate ceremonies - all of them were manifestations of Watson's own overcompensating insecurities. An awkward young man from a family with little money, he started out in a career that was the punchline of countless American jokes: the traveling salesman. Not until he was hired in 1896 by the National Cash Register Company in Dayton, Ohio, did Watson start to acquire the poise and polish that he would demand of his own executives decades later.

But his career at "the Cash," under the tutelege of its chairman, John H. Patterson, was very nearly his ruin. National Cash Register had a virtual monopoly in the manufacturing and sale of its product, which was becoming increasingly popular among American retailers. Unfortunately, the machines were built so solidly that they rarely wore out. Companies selling secondhand cash registers began to steal business from it.

So, in 1903, Patterson drafted Watson to run an elaborate scam. After ostensibly resigning from the company, Watson set up a chain of used cash register stores that was secretly backed by National Cash Register. By paying more for secondhand machines and selling them for less, Watson drove virtually all of Patterson's competitors out of business. He seems never to have doubted the legality of what he was doing. But when an angry ousted executive started talking to the Justice Department, the scheme figured in a 1912 federal grand jury indictment of Patterson and more than two dozen of his executives, including Watson.

In February 1913, Watson, Patterson and all but one of the other executives were convicted of criminal antitrust violations. Watson, newly married, faced up to a year in prison.

Somehow, in 1914, he nevertheless persuaded an unreconstructed trust-builder named Charles Ranlett Flint to hire him to try to save a rickety business-machine trust that Flint had assembled in 1911. The conglomerate included the Computing Scale Company of America, which made scales that calculated the price of products sold by weight; the International Time Recording Company, which made the time clocks on which workers punched in for the day; and the Tabulating Machine Company, which used punched holes in rectangular cards to sort information - "the forefathers of mainframe computers," notes Mr. Maney, a technology columnist for USA Today.

FLINT called this ailing hodgepodge the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company. And in a remarkable decision - one cannot imagine it being replicated in this post- Enron era - he hired the energetic and supremely confident convicted felon, Thomas J. Watson, to bring the company back to life. Watson, whose conviction was later overturned, succeeded beyond anyone's imagination, except his own. Seeing the future in his little tabulating-machine company, he invested lavishly in research and expanded wildly, even in the face of the Depression.

Mr. Maney observes that "Watson borrowed a common recipe for stunning success: one part madness, one part luck, and one part hard work to be ready when luck kicked in."

The book draws on extensive corporate records to capture Watson's self-absorbed monologues to his senior executives, giving the reader an immense sympathy for the men and women who endured them. With I.B.M.'s cooperation, Mr. Maney seems to have inspected every letter, memorandum and index card that passed through Watson's hands. But the bulkiness of the research only occasionally breaks through the elegant fabric of the storytelling.

Watson - a tyrant in the boardroom, a charmer on the dance floor, a sponge for sycophantic flattery, a genius at selling an idea - emerges as an infuriating, sometimes pathetic but always fascinating business icon. For those who loved "Father, Son & Co.," this is an essential and readable companion book. Call it "I.B.M.: The Prequel." (New York Times, May 12, 2003)

IBM for decades had a distinct corporate personality, and the leader in driving that culture was Thomas Watson, Sr. Other books have described this irascible man, yet this biography by a technology journalist uses recently discovered and wonderfully detailed corporate log books to flesh out his contradictory persona. Watson was a short-tempered tyrant who surrounded himself with yes-men and managed an increasingly complicated company by instinct. Yet he inspired loyalty and enthusiasm through his relentless optimism and willingness to hire ordinary young people and give them a chance. He made IBM one of the first companies to accept women in its training programs, in the1930s no less. And when managers resisted hiring the first women graduates of the programs, he angrily fired every man who graduated the same year. Maney notes that IBM's dominant position in a booming industry may have played a large part in persuading employees to tolerate Watson's unpredictable behavior. But the author's delightful anecdotes showcase the quirky, human side of what became a major knowledge-based company. (Harvard Business Review, May 2003)

"...excellent use of transcripts...should be recommended reading for anyone who seriously wants to be a business mogul..." (Economist, 10 May 2003)

"...formidable in its research, vivid, insightful and often hilarious..." (Management Today, June 2003)

"...an intriguing study of the man who made IBM, Thomas Watson..." (New Scientist, 7 June 2003)

"Maney, a USA Today technology columnist, has written a superb biography of Thomas Watson Sr., who took over the small Computer-Tabulating-Recording (C-T-R) Company in 1914 and fashioned it into the giant corporation we know today as International Business Machines (IBM). Watson had come to prominence for his work at National Cash Register (NCR), but owing to his involvement in a federal antitrust case, was forced out of his job. This might have destroyed a lesser man, but not Watson, who quickly moved on to C-T-T. A lifelong salesman, Watson always paid close attention to his company's customers, but he also felt that employees were equally important, offering high wages and good benefits. Although his management style was often regarded as imperious, he is credited with founding IBM's famous corporate culture, which enabled the company to succeed. As he aged, be became increasingly stubborn and brooked no dissent, which led to some terrible misjudgments, most notably his involvement with IBM's German subsidiary and receipt of a medial from